|

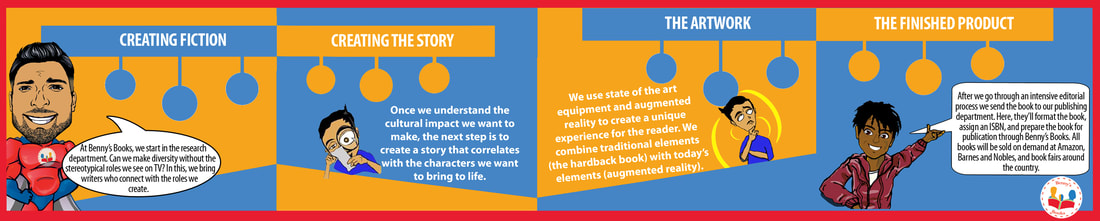

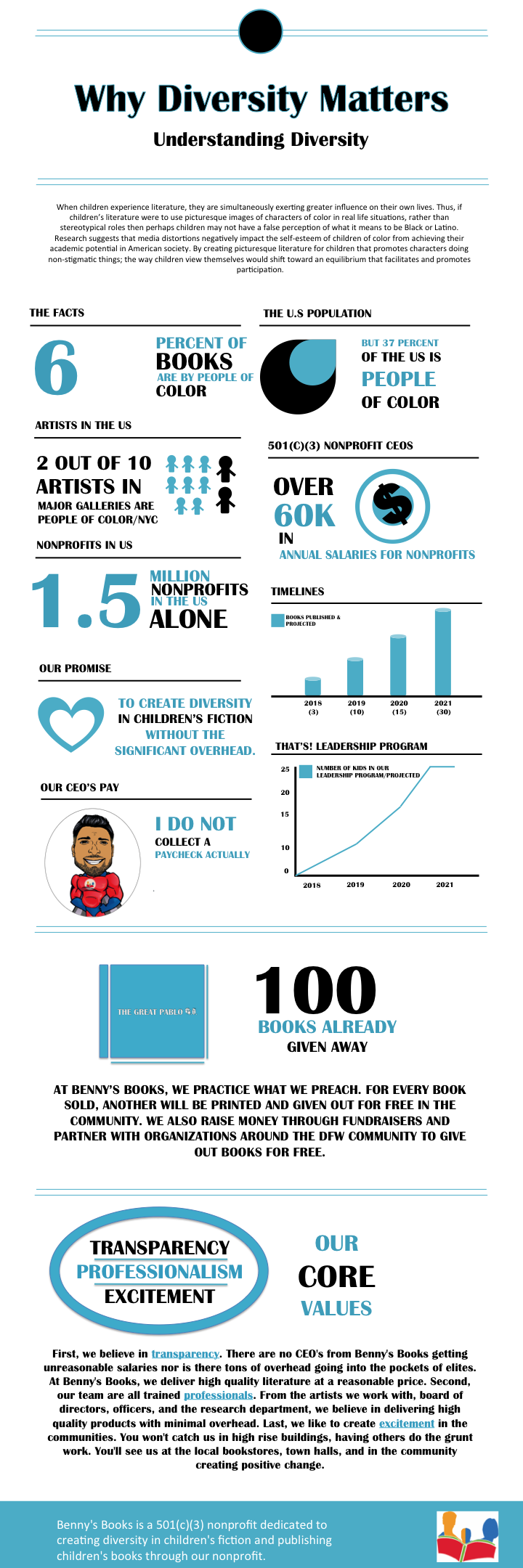

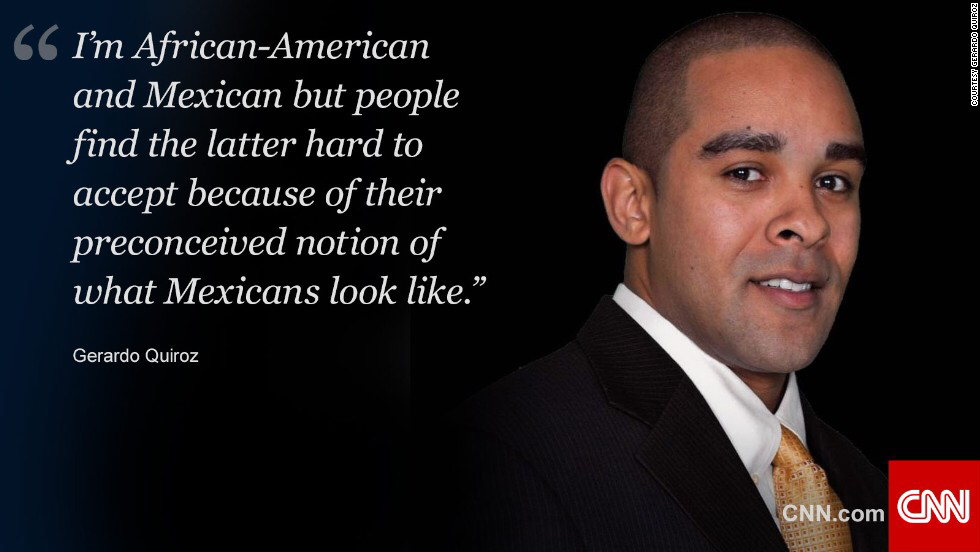

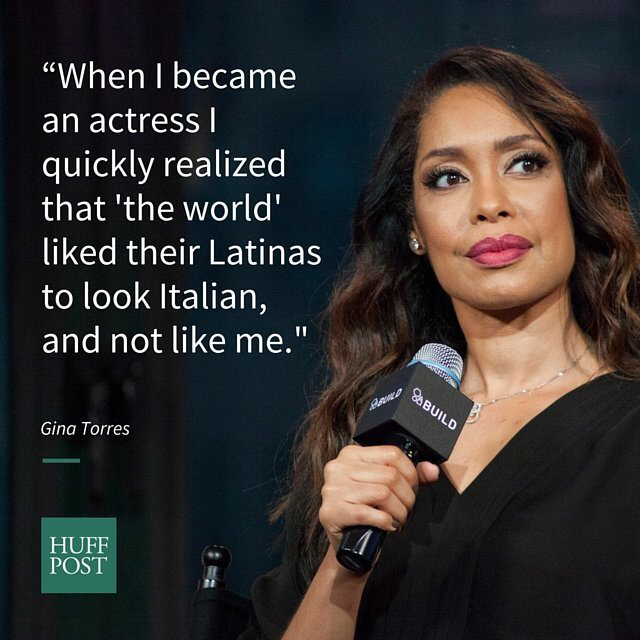

Books, and story telling in general, are a central part of childhood.[1] Stories play a central role in developing formative experiences in the lives of many children.[2] “[C]hildren’s books, because of their mythic power, because of their capacity to instill resources that echo throughout our life, are a crucial point of origin for [the] life-long practices [of adult life and law].”[3] By promoting literature to children at a young age—particularly from the transitional stage of toddler to student—within the private and public sphere encourages the beginning of independent reading.[4] When children experience literature at this transitional stage, they are distinguishing between parental rules and the rules of society, thus they are simultaneously exerting greater influence on their own lives while naturally and forcefully adopting to the existence of social rules.[5] One source of literature that influenced children’s perception of human rights is Dr. Seuss. Dr. Seuss would use comic illustrations, nonsense words, and outrageous plot elements to entice children; however, the stories possess real life aspects that children encounter, such as “discrimination, exploitation, loneliness, fear, and abandonment.”[6] Further, Dr. Seuss depicts a child with individual rights as the protagonist rather than as a person attached to a parent.[7] Many of these narratives have reoccurring themes that teach, “Core human rights principles and reinforce the idea that one should respect the rights of others.”[8] But beyond human rights and the “canonized white males,” works by minority authors can “yield valuable contrasting views of cultural artifacts.”[9] If children’s literature were to use picturesque images of Hispanic characters in real life situations, rather than stereotypical roles such the hot-blooded sexy characters, macho men, gang-members, drug dealers, or illegal immigrants, then perhaps children may not have the false dichotomy of what it means to be Latino.[10] Promoting these stereotypes creates a stigma that signifies that that person "is not quite human."[11] Further, enforcing these stereotypes as the norms carries a deeply negative reaction. Research suggests that media distortions negatively impact the self-esteem of African-American children from achieving their academic potential in American society.[12] Like Dr. Seuss, the characters in the children’s books can explore real life situations by surveying Latino history, cultural contributions in American society, or important Latino leaders in America, like Cesar Chavez or Nydia Velasquez.[13] By creating picturesque literature for children that promotes Hispanic characters doing non-stigmatic things, the paradigm of the perception of human rights, and the way children view the law, would shift toward an equilibrium that facilitates and promotes participation. Moreover the dynamic of storytelling between parent and child cannot be undervalued. Studies have shown that parental involvement with a more-involved structure at home correlates with a child’s grade improvement and higher self-esteem.[14] Further, the poverty rates in Latino are high; studies conducted have shown disproportionately high rates of illiteracy linked to children in poverty.[15] Some professionals view a lack of parental involvement by Latino parents as not caring, but other factors, like the parent’s own educational level, language deficiency, or unfamiliarity within the school system, lead to this lack of parental guidance.[16] Therefore the role of the proposed picturesque books should have an emphasis on different languages, such as English and Spanish, which would encourage the reading dynamic at home to continue. But even if only one language is spoken at home, studies have found that “young children who hear more than one language spoken at home become better communicators.”[17] Ideally, the practicality of picturesque books with minority-driven protagonists should not be exclusively for Latino children. All children should be exposed to different cultures in literature as some authors have suggested that children stories offer a way to imagine other worlds and differing “suppositions.”[18] To children, “the real and the imaginary are not always distinct categories, but rather closer points on a continuum; children easily pass back and forth between real and pretend, factual and fictional.”[19] By exposing all children to these imaginary tales, it enables children to get immersed in alternative realities and emerge as slightly different people.[20] Thus by creating applicable children’s books that enable a different culture could serve as a catalyst to “operate as the origins for social rituals, ideological creeds, and legal principles about justice, legal autonomy, punishment, and rights” among all.[21] Creating literature tailored for Latino children can alleviate some of the issues that Latino face. But such creation can only exist if the general public is made more aware of Latino literature and movements. The Chicano movement in the 1950s and 1960s was largely successful to the general public directly in part to the influence of the African-American fight for social justice.[22] As Latinos progress in the age of technology and social media, Latinos again have to look at today’s successful movements to make the general public more aware. More importantly, Latinos have to fully understand their identity of “being Latino” and understand how history has hindered and distorted Latinos perception of the law. To get a grasp on such knowledge would not promote Latinos to “overthrow the United States government” or “promote resentment toward a race or class of people”, but encourage Latinos to build a better future for their children.[23] BIBLIOGRAPHY: [1] See Johnson, supra note 1, 5, 5 n.12; see also e.g., Paulo Freire, The Importance of the Act of Reading, 165 J. Educ. 1, 8 (Loretta Slover trans., 1983) (reflecting on the “importance of the act of reading” in shaping one’s development). [2] Id. [3] Id. at 14; see also Desmond Manderson, From Hunger to Love: Myths of the Source, Interpretation, and Constitution in Children’s Literature, 15 Law & Literature 87, 95 (2003). [4] Id. at 16 [5] Id. [6] Id. at 15. [7] Id. at 2. [8]Id. [9] David Ray Papke, Problems With an Uninvited Guest: Richard A. Posner and the Law and Literature Movement, 69 B.U.L. Rev. 1067, 1086-87(1989) (reviewing Richard A. Posner, Law and Literature: A Misunderstood Relation 1989)). [10] Ediberto Roman, Who Exactly Is Living La Vida Loca ?: The Legal and Political Consequences of Latino-Latina Ethnic and Racial Stereotypes in Film and Other Media, 4 J. Gender Race & Just. 37, 39-40(2000). [11] See Johnson, supra note 1, 46; quoting Erving Goffman, Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity, 2 (Simon & Schuster 1986). [12] See Roman, supra note 178, at 64. [13] Veronique de Miguel, 5 Hispanic Leaders That Everyone Should Know, Huffington Post (Oct. 15, 2003 9:49 PM), http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/10/15/hispanic-leaders_n_4100409.html. [14] See Tinkler, supra note 66, at 3. [15] Id. [16] Id. [17] Jann Ingmire, Children exposed to multiple languages may be better natural communicators, UChicago News, (May 11, 2015), http://news.uchicago.edu/article/2015/05/11/children-exposed-multiple-languages-may-be-better-natural-communicators. [18] See Johnson, supra note 1, at 39. [19] Id. [20] Id. at 41. [21] Id. [22] Ian F. Haney Lopez, Protest, Repression, & Race: Legal Violence and The Chicano Movement, 150 U. Pa. L. Rev. 205, 214 (2001). [23] See Salinas, supra note 60, at 301-03.

In 1973, an officer observed David and Santos Rodriguez hanging out behind a gas station.[1] The officer called in the description and two officers, Roy Arnold and Darrell Cain, entered the Rodriguez house and arrested the two brothers.[2] David Rodriguez, Jr, the older brother of Santos testified that the officers handcuffed them behind their backs and that Santos was placed in the front seat of the patrol car with Officer Arnold.[3] Then they were taken back to the gas station where Santos was asked a series of questions.[4] Officer Cain was in the backseat with David when he took out his pistol, opened the cylinder, and twirled it.[5] David stated that he could see bullets in the cylinder and saw no empty chambers.[6]Cain shut the cylinder and aimed it at Santos’s head, who remained in the front seat.[7] Cain told Santos to tell them if he and his brother had burglarized the service station in which Santos denied.[8] Cain then clicked the pistol, stated that he had a bullet in it and that Santos needed to “tell the truth.”[9] Cain then clicked the gun and the gun fired, striking Santos in the head.[10] Cain jumped out of the patrol vehicle and stated, “Oh, my God.”[11] At trial, Cain asserted that he unloaded the weapon and tried to “make him tell the truth,” but this was disputed by David who never saw Cain unload the weapon.[12] After the shooting, Cain stated that he reloaded the pistol before another officer took the pistol from him.[13] But the officer, who grabbed Cain’s pistol within eight to ten seconds of shots being fired, unloaded the weapon and found five live rounds and stated he never saw Cain put the bullets back in the pistol.[14] After the shooting, the gas station was dusted for fingerprints and “neither the fingerprints of the deceased nor those of David Rodriguez were found.”[15] Santos and David were most likely innocent, but a twelve-year old, unarmed, handcuffed child was murdered, while his brother, a mere few feet away, watched a police officer carry out the execution. Protests erupted, one march particularly turned violent, five officers were injured, and more than 30 people arrested.[16] The low sentence—a five-year sentence—for a murder with malice charge of Santos Rodriguez was another stain within the criminal justice system towards the Latino community.[17] Again, the message was clear to many within the community: Latinos, including children, do not have much personal worth. Injustice in the criminal system is nothing new for Latinos, traffic stop data in 2001 indicated Hispanic drivers in San Diego had a thirty-seven percent greater chance of being stopped compared to white drivers.[18] Further, the study indicated Latino’s success rates for warrants were thirty-six percent whereas whites had a success rate of fifty-three percent.[19] But despite the large difference, Latinos were search warrant subjects in forty-three percent of the cases compared to whites, who were subjects of search warrants in only thirty-five percent of the cases.[20] Predictably, a 2001 study of the U.S. penal system indicate that Latinos also represent the fastest-growing segment of the U.S. prison population and that Latino men are four times as likely to be sentenced to prison during their lifetime compared to non-Hispanic white males.[21] Further, a study of twelve counties in Texas found that Hispanics represented forty percent of the juvenile population and that forty-three percent of the juveniles had cases adjudicated by the court.[22] Moreover, Hispanic juveniles were more likely to stand trial as an adult than Whites—even if they were disposed for the same offense, were the same age, and had a similar record in the juvenile system.[23] Most of the juvenile offenders surveyed faced barriers within the school system and half of the offenders experienced hardship within their homes or community.[24] Low educational attainment and high poverty, precursors to hardships within the home and community create a greater likelihood of contact within the criminal justice system.[25] This data conclusively demonstrates that Latinos are facing a discriminatory criminal justice system within their community that needs criminal justice reform. In Dallas, city and police officials have dramatically reformed the police department’s practices in response to the shooting of Santos Rodriguez.[26] For example, questioning of juveniles now requires a magistrate judge’s approval and in 2013, almost half of the 3,485 sworn police officers are minorities.[27] But changes to the overall police department are not enough, states with a significantly large Latino population that share the overall population like Texas, must shift their focus to Latino children, since these children will someday be the state’s future workers and taxpayers.[28] BIBLIOGRAPHY: [1] Cain v. State, 549 SW 2d 707, 710 (Tex. Court of Criminal Appeals 1977). [2] Id. [3] Id. [4] Id. [5] Id. [6] Id. [7] Id. [8] Id. [9] Id. [10] Id. [11] Id. [12] Id. at 711 [13] Id. [14] Id. [15] Id. [16] See Silverman, supra note 13. [17] Id. [18] Donna Coker, Foreword: Addressing the Real World of Racial Injustice in the Criminal Justice System, 93 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 4 827, 835-837 (2003). [19] Id. [20] Id. [21] Michael J. Coyle, Latinos and the Texas Criminal Justice System, National Council of La Raza Statistical Brief, 1-2 (2003) (downloaded at research.policyarchive.org). [22] Id. at 10. [23] Id. [24] Id. [25] Id. at 3. [26] See Silverman, supra note 13. [27] Id. [28] See Coyle, supra note 161, at 16.

The 1900s saw a sweeping amount of oppression for all minorities, with the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, Jim Crow laws, and many other laws aimed at disadvantaging people of color. Latinos were no exception to this rise of oppression. Latinos have had their property, history, and culture systematically taken from them from government and legal actors.[1] In the 1920s, Latinos in Texas “could not enter restaurants, parks, or even public swimming pools reserved for Whites.”[2] Moreover, Latino children in school were subjected to the “No Spanish Rule” in which punishment occurred if children were caught speaking Spanish.[3] As a result, many Latinos who are native born do not speak Spanish, nor have a firm understanding of their cultural identity.[4] School experiences can have a positive and long-lasting effect on the social and educational development of students; therefore barriers placed on Latinos at school had a negative effect in adulthood.[5] Seven years before the Supreme Court's landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education, Mendez v. Westminster challenged the validity of the separate but equal clause.[6] The Mendezes brought a class-action lawsuit with other Latino families against four Orange County school districts in California that had separate schools for Whites and Mexican-Americans.[7] Their case went all the way to the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals where the Court ruled in favor of Mendez because it violated the Fourteenth Amendment by “ . . . depriving them of liberty and property without due process of law and by denying to them the equal protection of the laws.”[8] Segregation in those districts ended and the rest of the state followed.[9] Unfortunately studies indicate that Latinos are still not ranking comparatively to other races. Latino students have the highest annual high school dropout rate at 7.1% (higher than any other ethnic group) and “the percentage of Latino adults ages 18 to 24 are no longer enrolled in school and who have not completed high school is more than double that of any other ethnic group measured by the [US] census.”[10] This evidence suggests that the mis-education of Latino children may indeed be the norm. A 2003 study shows that Latinos 25 years of age and older find themselves at the bottom of the educational rankings.[11] Only 11% of Latinos have a college degree and 57% have a high school education.[12] Concentrated poverty within particular school zones is a direct cause of educational inequality, a reality evident within the Latino community—home to the highest percent of impoverished students.[13] These results indicate the common feeling amongst the Latino community in that “schools try to brainwash Chicanos. They try to make us forget our history, to be ashamed of being Chicanos Mexicans, of speaking Spanish. They succeed in making us feel empty, and angry inside.”[14] In 2013, a Pew study estimated that 40% of Latinos do not speak Spanish; however, this number might be even higher for native-born Latinos since it is estimated that native-born Latinos outnumber first generation Latinos by a two-to-one ratio.[15] Research has shown that Latino children with low parental involvement is linked to low academic achievement, therefore, schools “must be seen as a potentially key preventive and protective resource for [these] children.”[16] Adolescents who are less comfortable or have a negative correlation to their ethnicity have lower self-esteem.[17] With many Latinos disengaged with their culture and unclear of their own ethnicity, ethnic studies need be a priority amongst the general population, particularly because the lack of ethnic studies remains a barrier for Latino children. Despite the rich Latino history and heritage of the Southwest, only seven percent of the secondary schools surveyed in the 1960s included a Mexican American history course in their curricula.[18] For example, in Tucson Arizona—a city that is predominately Latino—created the Mexican-American Studies Department (MASD) that encouraged “equitable educational ecology" and a chance for students to develop a critical consciousness.[19] MASD offered a curriculum that challenged the status quo and promote a better bond between student and teacher.[20] But ten years later, Arizona's Republican leadership attacked MASD as “being segregationist, racist, and desirous of overthrowing the U.S. government.”[21] Legislation was proposed that attempted to prohibit the use of any curriculum that focused on "voices and experiences of people [of] color."[22] However, some students disagreed, arguing that the course offered made them more aware, more respectful, and “more accepting and open to different ethnicities, different ways of life[,] and different traditions."[23] But critics like previous Attorney General Tom Horne of Arizona disagreed; asserting that if the teaching is about “la raza, how is that developing respect for other ethnicities?"[24] Horne made these assertions without ever visiting a MASD classroom, instead only gaining knowledge through second hand sources.[25] The attacks on the MASD program led to H.B. 2281, a bill that proposed individuals should “not be taught to resent or hate other races or classes of people.”[26] Despite its rhetoric that created a barrier for the MASD program, the bill was passed. As a result, MASD came under fire by Horne who “repeatedly and publicly stated that he intends to find the [MASD classes] to be in violation of the statute.”[27] Critics of the bill argued that Board of Education, Island Trees Union Free School District v. Pico, sets precedent in that “the State of Arizona confronts an almost insurmountable challenge on First Amendment and Equal Protection grounds in defending [the] harsh legislative measure to eliminate the ethnic studies program. The First Amendment prohibits state action that infringes on a right to express oneself.”[28] In Pico, the Supreme Court affirmed the Second Circuit’s decision that the local school board had no right in its removal of library books from high school and junior high school libraries.[29] After members of the local school board attended a conference by a politically conservative parents' organization, the board decided to remove books that were deemed “objectionable and anti-American, anti-Christian, anti-Semitic, and just plain filthy."[30] Pico and other plaintiffs, students, filed a claim under the Civil Rights Act claiming that their First Amendment rights had been violated.[31] In the Supreme Court opinion, Justice Brennan, writing for the majority, stated that “local school boards may not remove books from school library shelves simply because they dislike the ideas contained in those books and seek by their removal to prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion."[32] The Court, citing other previous cases stated, that: (1) student's freedom of expression is not to be restricted because of the fear that those views might upset other students and (2) school officials must establish that their actions are “something more than a mere desire to avoid the discomfort and unpleasantness that always accompany an unpopular viewpoint."[33] Studies conducted on the MASD curriculum of more than 26,000 students, found that students with lower prior achievement benefitted significantly more from taking MAS courses.[34] Further studies have shown that by removing these programs “could potentially harm the most academically vulnerable students (i.e., those students whom the MAS program tended to serve)”.[35] Given the results of this study and the absence of a viable replacement, the needed discussion is how to replicate and expand the successes of this program beyond Tucson. Despite these numerous studies that encourage ethnic studies—in conjunction with the growth of the Latino population and the inequality of the education system among minorities, ethnic studies continue to be a barrier for Latino children. BIBLIOGRAPHY: [1] Lupe S. Salinas & Dr. Robert H. Kimball, The Equal Treatment of Unequals: Barriers Facing Latinos and the Poor in Texas Public Schools, 14 Geo. J. Poverty Law & Pol'y 215, 221 (2007). [2] Lupe S. Salinas, Language: Immigration and Language Rights: The Evolution of Private Racist Attitudes into American Public Law and Policy, 7 Nev. L.J. 895, 909 (2007). [3] . Id. at 917. Many young Latinos have stated their parents instructed them to learn only English since each parent had been punished at school for speaking Spanish on school grounds. In addition my father, Jose Robles Sr. was held back in first grade for not knowing “good English.” [4] Jens Manuel Krogstad, et al, English Proficiency on the Rise Among Latinos: U.S. Born Driving Language Changes, Pew Research Center Hispanic Trends (May 12, 2015), http://www.pewhispanic.org/2015/05/12/english-proficiency-on-the-rise-among-latinos/. [5] Robbie Gilligan, The importance of schools and teachers in child welfare, Child & Fam. Soc. Work 13, 14 (1997). [6] See Salinas, supra note 49, at 222. [7] Id. [8] Id. at 222-223; quoting Westminster Sch. Dist. v. Mendez, 161 F.2d 774, 780-81 (9th Cir. 1947). [9] Id. [10] Martin J. La Roche & David Shriberg, High Stakes Exams and Latino Students: Toward a Culturally Sensitive Education for Latino Children in the United States, 15 J. Educ. & Psychol. Consultation 2, 205, 206 (2004). [11] Lupe S. Salinas, Arizona’s Desire to Eliminate Ethnic Studies Programs: A Time to take the Pill and to Engage Latino Students in Critical Education About Their History, 14 Harv. Latino L. Rev. 301, 314 (2011). [12] Id. [13] Id. The researchers conclude that poor schools are a barrier to quality education since students in segregated minority schools were eleven times more likely to be in schools with concentrated poverty, but ninety-two percent of white students did not face that barrier. [14] See Salinas, supra note 7, at 287. [15] See Krogstad, supra note 53. [16] Barri Tinkler, A Review of Literature on Hispanic/Latino Parent Involvement in K-12 Education, (2002), available at http://www.buildassets.org/Products/latinoparentreport/latinoparentrept.htm. [17] See Salinas, supra note 60, at 315. [18] Id. at 314, the United States Commission on Civil Rights conducted research on the crisis of Latino educational attainment. [19] Id. at 301-02. [20] Id. at 301. [21] Id. at 304-06. [22] Id. at 307. [23] Id. at 309. [24] Id. [25] Id. at 308. [26] Id. at 304. [27] Id. at 312. [28] Id. at 318; see also Board of Education, Island Trees Union Free School District v. Pico, 457 U.S. 853 (1982); e.g. First Amendment provides in part: "Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press." Gitlow v. New York, 268 U.S. 652, 666 (1925). [29] Id. at 316. [30] Id. [31] Id. at 317; see also Pico, 457 U.S. at 871-72. [32] Id. at 317-18. [33] Id. at 319. [34] Nolan L. Cabrera et al., Missing the (Student Achievement) Forest for All the (Political) Trees: Empiricism and the Mexican American Studies Controversy in Tucson, 51 Am. Educ. Res. J. page 6, 1084, 1106 (2014). [35] Id. at 1109.

There is no denying that the rhetoric on Mexican-Americans has elevated in our political circles the last few years on many issues such as immigration, language, and residency; particularly with our undocumented counterparts. Many Mexican-Americans have since been homogenized with undocumented immigrants and have been mocked, ridiculed, and held responsible for the issues above. As a result, some Mexican-Americans have blamed undocumented immigrants for the nasty rhetoric they've heard instead of blaming those who continue to harass all Latinos, documented or not. However, what's important is for Mexican-Americans to understand their history in this country and how it impacts them and every other American or non-American. Here is a brief history not taught at our schools: The Spanish conquest of Texas in the 1500s included the dissemination of the Spanish language and Christianization among the many Native tribes in Texas.[1] This “Hispanicization” of the native population was facilitated by the intermarriage of Spaniards and Natives, adoption of Native children by "Spanish" families, and the capture of Native slaves.[2] Eventually this mixed race known as “Mestizos,” treated as second-class citizens by the Spanish, revolted and eventually obtained independence from Spain in 1821.[3] Soon after, Anglos migrated to Texas, partly because the Mexican government encouraged migration.[4] Racial-cultural tensions developed and Mexican-Anglo relations broke down, eventually leading the Anglos to declare war against the Mexicans.[5] The Anglos were victorious, but the Mexican government never formally recognized Texas Independence.[6] In 1846, President Polk, wanting to expand the U.S. and annex Texas formally, invaded and occupied Mexico, forcing Mexico to formally give up what is now known as Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and California through the Treaty of Guadalupe (Treaty).[7] The Treaty’s intended purpose was to give Mexico money for half of the land that was taken, Mexican’s full U.S. citizenship, and the right for Mexican citizens to keep their land.[8] As a result, 75,000 Mexicans stayed to become U.S citizens.[9] Unfortunately this treaty was not honored and many Mexican-Americans lost their homes because the courts, law enforcement, and government officials willfully ignored their pleas.[10] For example, the Texas Rangers often terrorized the Latino population, earning a reputation for shooting first and determining later if Mexican’s were ever armed.[11] Moreover, national leaders often warned against letting Latinos join in the ranks of White America.[12] Borderlands: La Frontera by Gloria Anzaldua is a book consisting of poems and historical reference to Latinos internal and external struggles in the U.S. The author describes the U.S. Southwest as “Aztlan,” the true homeland for Chicanos.[13] “This is my home this thin edge of barbwire. but the skin of the earth is seamless. The sea cannot be fenced, el mar does not stop at borders. To show the white man what she thought of his arrogance, Yemaya blew that wire fence down. This land was Mexican once, was Indian always and is. And will be again.”[14] The context of the poem describes a border between Mexico and the U.S. that is arbitrary because of the historical implications and the right of first possession. Here, the author makes the claim that the Chicano was here first; therefore, the land is the land of her people. She explains, “the oldest evidence of humankinds in the U.S.—the Chicanos’ ancient Indian ancestors—[were] found in Texas and has been dated to 35000 B.C.”[15] Further, the author describes the border as an unnatural boundary, one created by the “Gringo” that considers inhabitants as aliens—whether they possess documents or not.[16] But the poem goes beyond describing a border; the poem expresses anger, pain, and sorrow. She describes the retaliation of Mexican-American resisters who robbed a train in Brownsville, Texas, but only further increased the violence against Latinos.[17] Vigilante Anglo groups started lynching and murdering Latinos and thousands of Mexican-Americans fled to Mexico, leaving their only homes known behind.[18] The historical context of Latinos in America serves as an outline to understand the early beginnings of discrimination against Latinos. Further, the colonization of the Natives by the Spanish and then eventual colonization of the Mestizos by the Americans provide a roadmap to the complexity of the Latino identity.[19] Borderlands serves as a voice of the “Chicano,” expressing the injustices of Anglos on the Latinos native land. The social injustices of Latinos in its early beginnings continued to exist in the 1900s. Schools, a component of the bureaucratic system, were routinely segregated, racial identities stripped, and ethnic studies dismissed.[20] Just something to think about it in today's current climate about us as Natives, Mexicans, and Mexican-Americans. BIBLIOGRAPHY: [1] Jose Roberto Juarez, Jr., The American Tradition of Language Rights: The Forgotten Right to Government in a Known Tongue, 13 Law & Ineq. 443, 470-472 (1995). [2] Id. [3] Id. [4] See Salinas, supra note 7, at 272; citing Samuel Harman Lowrie, Culture Conflict In Texas, 1821-1835 59-60 (1967). [5] Id. Other factors were involved; Anglos encountered largely Catholic population, repealed slavery by the Mexican government, and the language barrier between the two. [6] Id. at 273. [7] Id. [8] Id.at 274, 274 n.26. The Treaty of Guadalupe was to give Mexican’s who chose to stay in the U.S. full U.S. citizenship and fifteen million dollars for the land taken. [9] Id. at 274. [10] Id. [11] Id. at 279. [12] Id. at 274. [13] See Anzaldúa, supra note 8, at 23. The author explains that the Aztecas del Norte, the largest single tribe in the United States, often identify as Chicano and see the U.S. Southwest as their true homeland (Aztlan). [14]Id. at 25. [15] Id. at 25, 114 n.3; citing John R. Chavez, The Lost Land: The Chicano Images of the Southwest, 9 (University of new Mexico Press, 1984). [16] Id. at 25. A “gringo” is a Spanish term used by Latinos to describe non-Latinos, usually White. [17] Id. at 30. [18] Id. [19] See Juarez, supra note 30; see also Salinas, supra note 33. [20] Lupe S. Salinas & Dr. Robert H. Kimball, The Equal Treatment of Unequals: Barriers Facing Latinos and the Poor in Texas Public Schools, 14 Geo. J. Poverty Law & Pol'y 215, 221 (2007).

Civil Rights in America is usually portrayed as a Black and White issue, but Latinos have engaged and transformed Civil Rights in ways not known to the general public. But even though Latinos have a rich history of creating change in our nation, why is it not widely known or celebrated? Why can't we name off several prominent leaders of the Latino community like we can in regards to the African-American community? And where is the unity at compared to other cultures? The question lies in the many barriers and complexities of what it actually means in being considered "Latino." LACK OF UNDERSTANDING THE LATINO CULTURE The history of Latinos in America is multilayered and rich; however, the Latino image is often portrayed as a “homogenized population,” negating the different linguistic, racial and ethnic distinctions within the Latino population. [1] For example, Latinos with “brown-skin,” prompt many Whites to think of Latinos as "members of the Mexican race," but being called “Mexican” is equivalent to calling someone an “American.”[2] However, the misconception of Latinos does not apply to just Whites, even Latino Americans themselves have failed to understand their own cultural and ethnic background. In America, roughly 52% of Mexican-Americans have identified as White, whereas in Mexico, only 9% identify as White.[3] The majority in Mexico identify as Mestizo—meaning that they are of European and Native American descent.[4] However, genetic studies performed in the general Mexican-American and Mexican populations have shown that Mexicans residing in Mexico consistently have a higher European admixture in average than Mexican Americans.[5] Clearly, the identity of Latinos has created confusion among the general population—Latinos included—and as a result, has inhibited the growth of the culture in America. LATINO IDENTITY Many of the issues surrounding identity have came down to determining if “being Latino” is a cultural, racial, or national origin distinction.[6] For example, there have been calls to action to eliminate racial classifications because the classification destroys the distinction between race and national origin.[7] Overall, some have argued that the terms “Latino” or “Hispanic” creates a category that is too broad, in which the legal system and its actors “conceptualize race.”[8] To elaborate, Latino discrimination has not been clearly identified among the general population on a large scale, partly because the media, courts, and politicians have framed civil rights as an almost exclusively black and white issue.[9] For example, the Texas Supreme Court declared in 1951, that the Fourteenth Amendment did not apply to Mexican-Americans, but only to Blacks and Whites.[10] Further, the African-American community has experience more success because their interethnic relations has not diminished their movement.[11] Nonetheless, the complex racial identity—in conjunction within a legal system comprised of actors that marginalize Latino’s rights—has continued to downplay discrimination among the general population. As a result of these identity issues and the lack of understanding of what it means to be "Latino", the general population is more likely aware of African-American literature and its movements rather than that of Latinos. BIBLIOGRAPHY: [1] Gloria Sandrino-Glasser, Los Confundidos: De-Conflating Latinos/as’ Race and Ethnicity, 19 Chicano-Latino L. Rev. 69, 71, 150, (1998). [2] See Salinas, supra note 7, at 286. “Mexican” is a nationality like “American,” and not a race, there are different races in the Mexican nationality. [3] U.S. Census Bureau, Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin: 2010, Table 2 (2010); Id. at 286 n.16, the Mexican population is currently listed as being sixty percent mestizo citing The World Almanac and Book of Facts 538 (Erik C. Gopel ed., World Almanac 2005). [4] Id. [5] Jeffrey C. Long, et al, Genetic variation in Arizona Mexican Americans: estimation and interpretation of admixture proportions, 84 Am. J. of Physical Anthropology 2, 141, 144 (1991); see also Joke Beuten, et al, Wide Disparity in Genetic Admixture Among Mexican Americans from San Antonio, TX., 75 Annals of Hum. Stud. 4, 529, 535 (2011). Genetic studies performed in the general Mexican-American and Mexican populations have shown that Mexicans residing in Mexico consistently have a higher European admixture in average (with results ranging from 37% to 78.5%) than Mexican Americans (whose results, range from 50% to 68%). [6] See Sandrino-Glasser, supra note 19, at 75-76. [7] . Ian F. Haney Lopez Race, Ethnicity, Erasure: The Salience of Race to LatCrit Theory, 85 Calif. L. Rev. 1143, 1149 (1997). [8] Id. at 1145-47. [9] Id. [10] Id. at 1143-1145. In 1954, lawyers with the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), took up a case where a Mexican-American (Pete Hernandez) was convicted by an all-white jury. The Texas Supreme Court held that the Fourteenth Amendment guaranteed the protection of only the White and Black class. The case was taken to the United States Supreme Court where the court delivered a unanimous opinion in extending equal protection to Pete Hernandez and reversing his conviction. The reasoning was not based on race alone, but that Hernandez belonged to a class distinguishable on some basis "other than race or color" that nevertheless suffered discrimination as measured by "the attitude of the community." [11] Kevin R. Johnson, Civil Rights and Immigration: Challenges for the Latino Community in the Twenty-First Century, 8 La Raza L.J. 42, 64 (1995). |

ABOUT:Benny's Books is a 501(c)(3) Nonprofit Organization that creates diversity in children's fiction and gives out children's books for free. Archives

November 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed